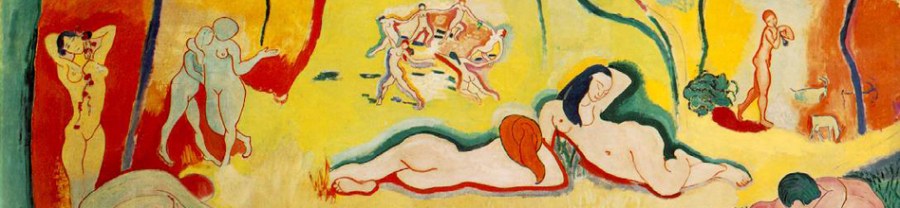

Henri Matisse is one of my all-time favourite artists.

His romantic impressionist paintings leave me feeling like I want to walk right into them. They make you want to dance naked holding hands in a circle, lie in a Garden of Eden and wear a fancy hat way too large for your face.

DESIGN OBSERVER HAS PUBLISHED AN ILLUMINATING, LONG-LOST INTERVIEW WITH FRENCH ARTIST HENRI MATISSE. READ SOME HIGHLIGHTS HERE.

In August of 1946, after the end of World War II, an art-obsessed American soldier named Jerome Seckler interviewed legendary French painter Henri Matisse. At the time, Matisse had been suffering from cancer for several years and was at work on his collaged cut-outs—specifically, large-scale works that would become Oceania, The Sky and Oceania, The Sea—which are now on view at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. In their extensive dialogue, Matisse discussed everything from the value of being a “starving artist” (“It is evident that in order to make good artists it is necessary that they not eat too well”) to the nitty-gritty of his creative process. The interview’s roughly 3,000-word transcript sat unpublished in a cardboard box for 70 years.

This year, Jerome Seckler’s son, Donald Seckler, unearthed the lost interview, which Design Observer has now published for the first time, in three installments.

In places, the interview turns into a heated debate—Seckler’s questions are challenging and provocative, and you can hear the ever-opinionated Matisse get a bit riled up. The artist’s comments range from the philosophical (“It is necessary that life be hard in order to form one’s character”) to the drily funny (“In America there are not enough bad boys”) to the self-reflective (“Do you think that I am neurotic? Is it seen in my paintings?”). Below are some highlights.

In part one of the interview, Seckler asks Matisse about the importance of subject in painting. “A book would be necessary to answer [this question],” Matisse replies. “The question is complex, very complex.” But he offers some opinions in this excerpt:

Henri Matisse: I think that art must not be a disagreeable thing. There is enough unhappiness in life to turn one towards the joy. One should keep the disagreeable, the unhappiness to himself. One can always find a pleasant thing. An unhappiness doesn’t remain. It makes experience. One doesn’t need to infect people with his annoyances. One should make a serene thing. One should make a stimulating art which leads the spirit of the spectator into a domain which puts him outside of his annoyances.

In part two of the interview, Matisse defends the starving artist, arguing that struggle builds a painter’s character:

Jerome Seckler: If the artist plays such an important role in society, don’t you think that a government subsidy should be paid the painter just like it pays any other government worker? He wouldn’t have to worry about where his next piece of bread was coming from. He could live a normal family life like any other person. He wouldn’t be at the mercy of a dealer. He should really be free to paint.

Henri Matisse: I am against ease. If one leaves the possibilities of getting a pension from the government for painting, to all the people who want to paint, all the Sunday painters will seize a brush. That is impossible. It is necessary that there be a straining. While giving to people who want to paint the facilities of doing it, it is necessary to put up a very strong barrier to prevent the invasion of the bad painter. Each time that a student who devotes himself to painting arrives at school for the first time, he should be given a volley of blows by a stick and after to lead him back to his home and he will see if he wants to begin again. If there was a test like that there would be a great many who would not return.

It is necessary that life be hard in order to form one’s character. That makes muscles. Art is a thing of exception. A great many people think today that they are artists because they see beautiful sunsets, or flowers. Today with the degree of civilization to which we have reached, everybody is sensitive to art, but that doesn’t mean that they are capable of making all that.

In this excerpt from part three, Matisse disses young copycat painters and discusses his painting process.

JS: When we look around at the young contemporary painters we see the tremendous influence of your painting. You have certainly helped change the direction of painting especially by your color.

HM: It is not my fault. I didn’t do it on purpose.

JS: Do you use color scientifically? What is your theory of color, especially as regards your conception of perspective?

HM: No, I don’t use color scientifically. And I have no theory of color. I haven’t any theory, even of drawing. That comes only from what I know what to look forward to. I work while waiting what will come. When I began painting, I copied the paintings in the Louvre and I finished by clarifying all that I thought and to see that color is a very beautiful thing. Why mix up the colors. Why trouble with all that. Why not utilize these colors as they are naturally. I searched for my combinations with combinations of colors which do not destroy themselves. In my [spirit], perspective is made in my head and not on the paper. That depends on you and the ideas you have. The most simple things are the most difficult.

The interview is well worth a read in its entirety—head to Design Observer for parts one, two, and three of the extensive talk.

The true work of ART is but a shadow of the divine perfection – Michelangelo.

You must be logged in to post a comment.